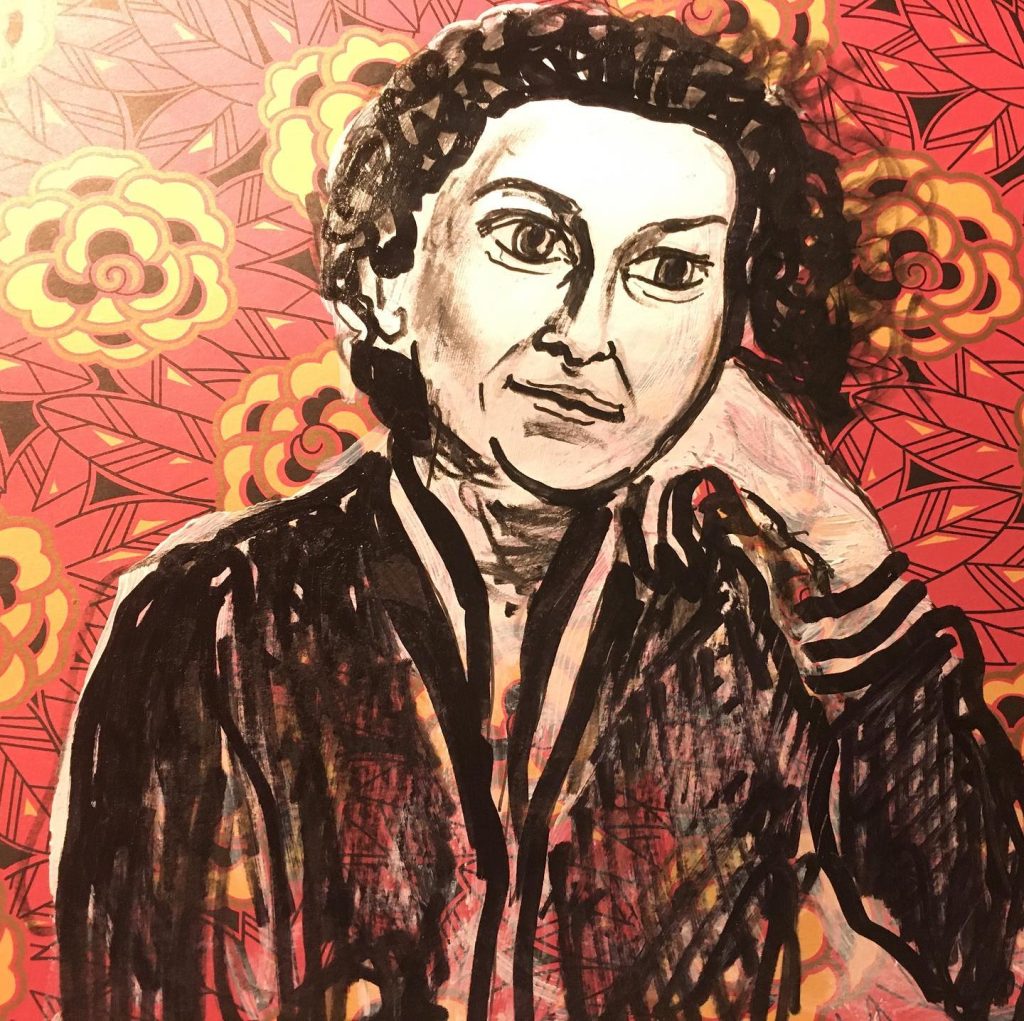

Icons of the Belarusian revolution: a conversation with Xisha Aniolawa, the artist

Ksenija Anhielava, also known under the artistic pseudonym of Xisha Aniolava. Born on September 12, 1975 in Miensk. In 1996 she graduated from the theater school of the Belarusian State Academy of Arts. An actress, a radio host, and an artist; a mother of two children, Xisha has been painting since 2011. You can find the work of both Ksenija and her mother Alena Piatrosava on the walls of churches in Belarus, Ukraine, Russia, Georgia, France, Germany and Poland. Since November 2020 Ksenija creates portraits of Belarusian political prisoners. She lives in Warsaw and works as a tour guide in the “White House” of the Łazienki Królewskie Park and the Palace complex.

— Xisha, you studied icon painting, you wrote icons and frescoes for Orthodox churches and even created mosaics. So where is you work displayed now?

— Indeed, I painted a lot of icons for Belarusian churches, I studied at an icon painting school to learn this skill. My dear late mother Alena Jurjeŭna Piatrosava and I made mosaics and frescoes for churches together. She was an architect, worked with stone, she studied the history of Belarusian architecture as a scientist for a long time and then she started making mosaics… She said that all her previous life had been leading to it. My mother and I had a wonderful tandem, one which is unlikely to be repeated, and it was a source of great happiness not just for me but also for my daughter. All our joint work creates a special memory for me. For example, the entire facade of the church in Rubiaževičy is completed with mosaics we have created. It is only a small church which was converted from a farm building, which stands on the bank of a river. You can also find our joint work in churches of Ratamka, Rubiaževičy, Novaja Myš, Plisa, Ščarca and some other small rural churches. Here, in Warsaw, I painted the chapel at the Stanislaw Kostka Lyceum. I painted many icons on slate because then they can withstand the outdoor conditions of preservation really well which means they can be displayed on buildings facades. At a certain time, we turned out to be persons non grata at various Orthodox exhibitions and events in Belarus, because we stuck to our style of painting, which was close to the local one [Belarusian] rather than following Moscow led icon painting trends, which were considered worthy of distribution.

— How did the Belarusian revolution of 2020 affect your work?

— Making art is a routine for me now, in a good sense of the word. Following the events of 2020, I painted and created art to manage my anxiety and emotional upheaval. Those tragic events events prompted action (as in Paul Tillich works: “something must be done, otherwise we will fall into despair, from which there is no way out”). For me, creativity is a cure for despair and powerlessness. Now I try to work every day as I don’t want to stop, I don’t want to get tired. It feels as if some kind of engine has been started, but this is a phenomenon not of a “spring” nature, but of a longer-lasting potential. As well as that now my creative mood is more of stable nature, nothing scares me. I am already safe here in Poland.

— Were you threatened to be arrested back in Belarus?

— I was not directly threatened, but there were many warning signs and then a critical moment came when it became clear that I had to leave if to make sure that my children would still have their mother. I am a single parent and in Belarus there are many cases when children of political prisoners are taken to care.

— How did you begin painting portraits of Belarusian political prisoners?

— I am painting them because I made such a promise, a vow to God, and this is the second such vow in my life.

The first time I gave it after the protests of 1996, when talented artists were kicked out of the Belarusian Academy of Arts for political reasons. My best friend Jan Cichanovič was one of those artists. These were the first protests against the coup d’état carried out by Lukašenka, who destroyed the parliamentary republic in Belarus. The artists were greatly humiliated then, some had to flee the country. Jan soon died in exile, and his father, Hienrych Cichanovič, also left this world quickly because of such a loss. After this first wave of repression, I decided – if Janka [short name for Jan] can no longer paint, then I will paint, because I he wasn’t just my friend, he was also a teacher…

And for the second time, I vowed to “continue the legacy” after the murder of Raman Bandarenka in 2020. It was as if I began to feel responsible for everything that was happening, so that everything that we experienced and did was not in vain.

It seems to me that when you see our political prisoners “face to face” it can leave a deep impression on you. We read and hear about our prisoners, but I hope that when you see a portrait, you are able to perceive that person in a picture a different way, because, while painting, the artist gave a piece of her soul amd mixed it with a prisoner’s personality. When I draw, I hope that the “chain from you-to-me-from-me-to-you” will expand far beyond. And these chains are very humane, because there is a difference between just reading poetry with your eyes and seeing someone reciting it.

— As an artist, have you always been close to genre of portraits?

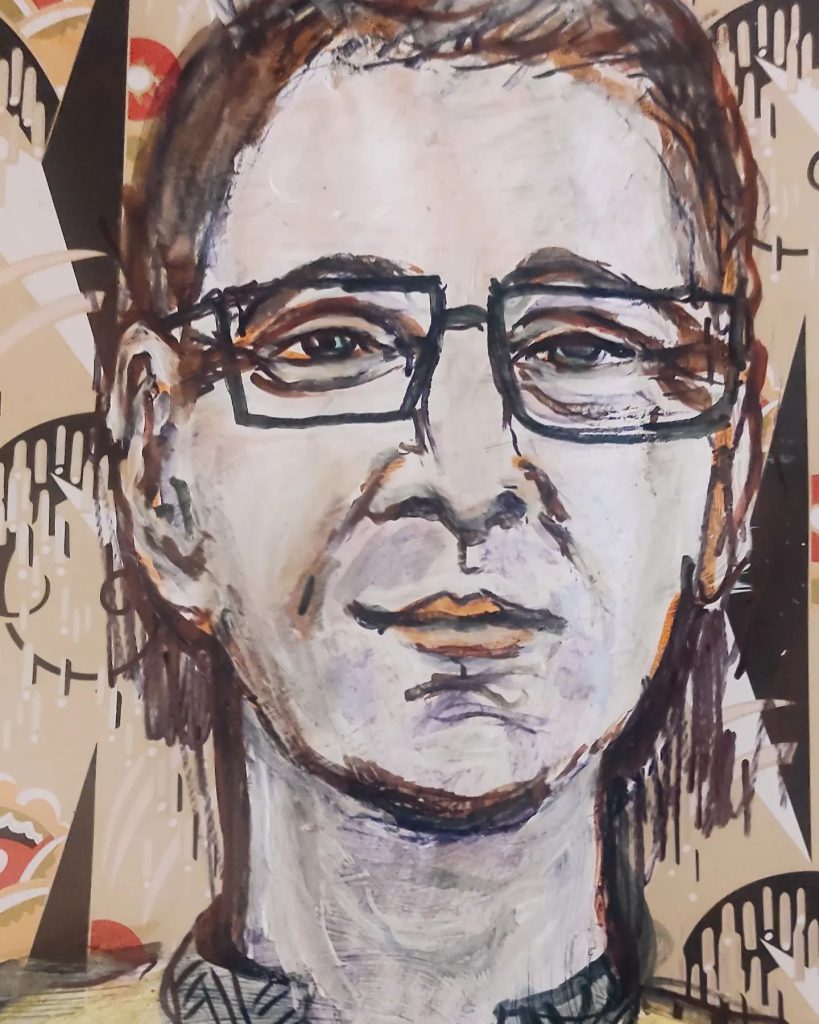

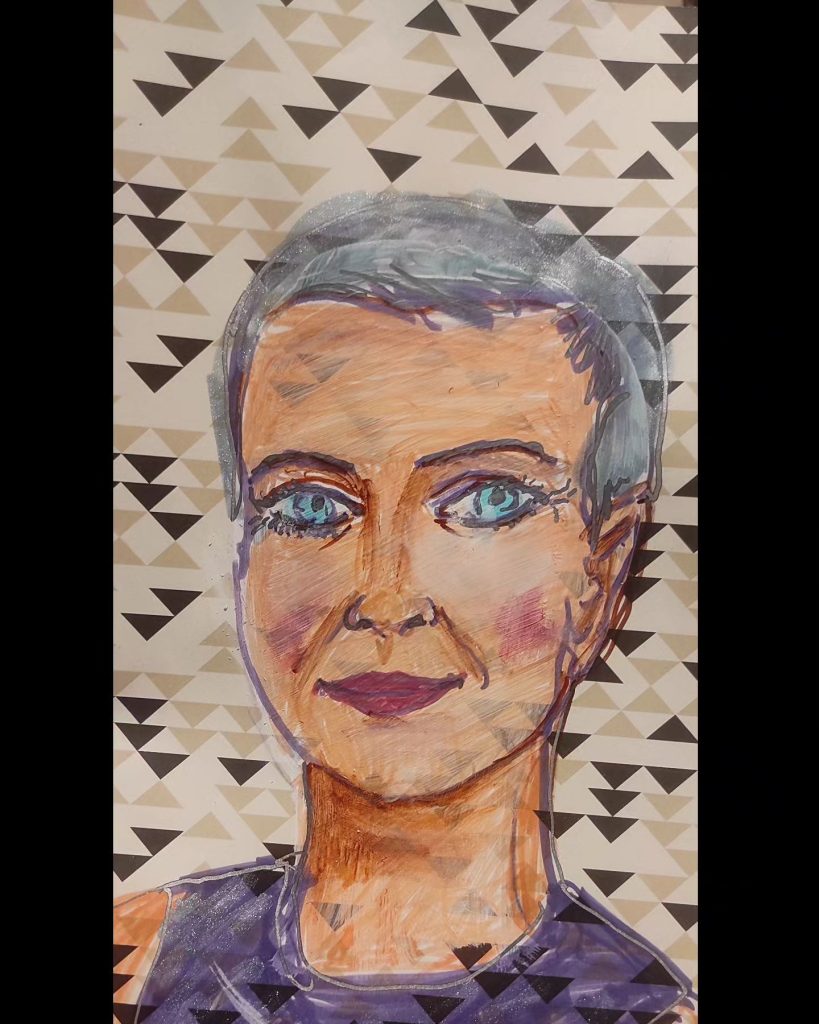

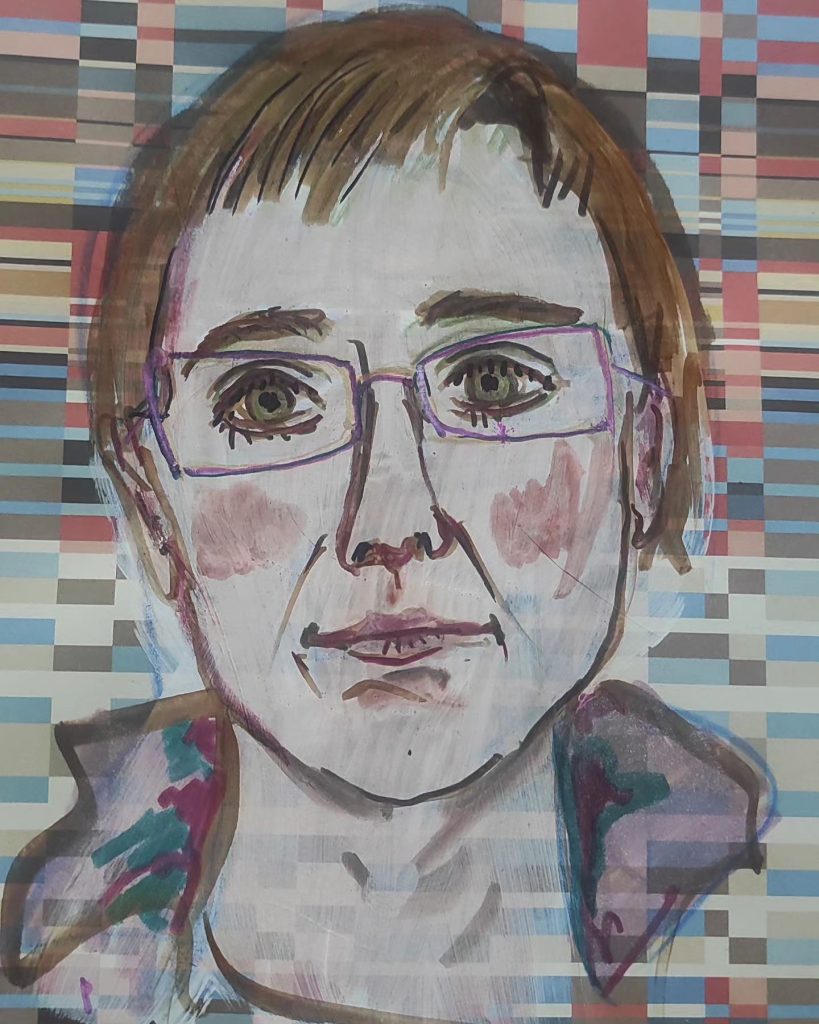

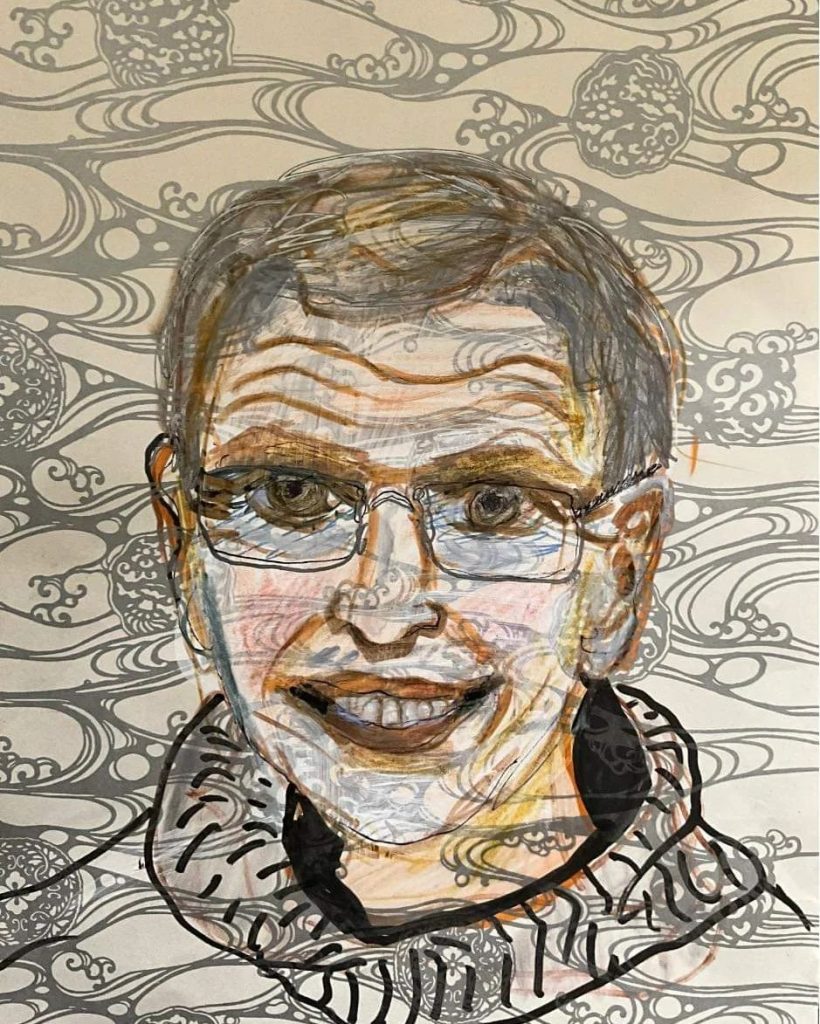

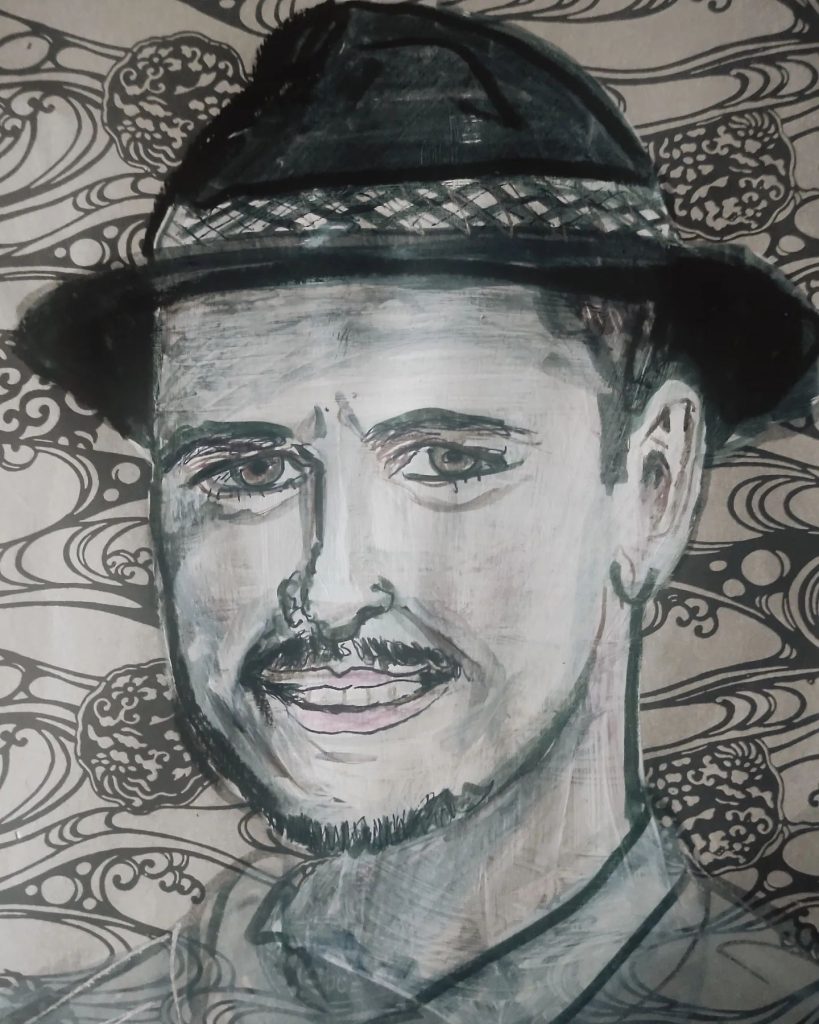

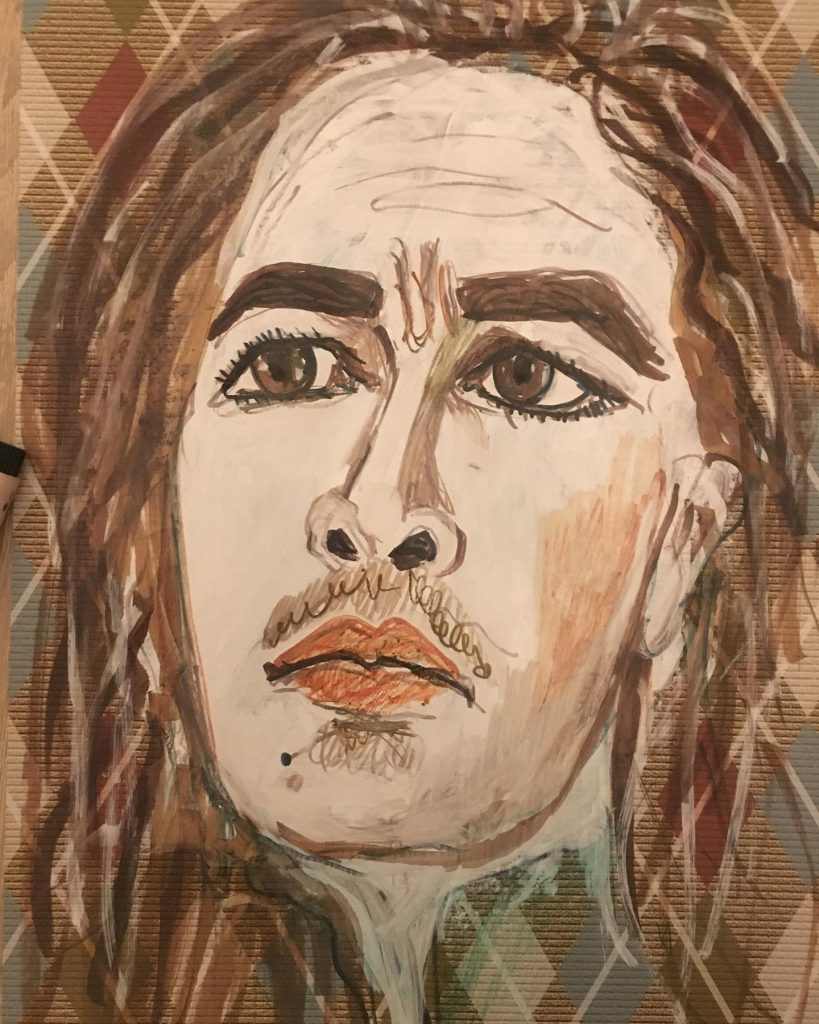

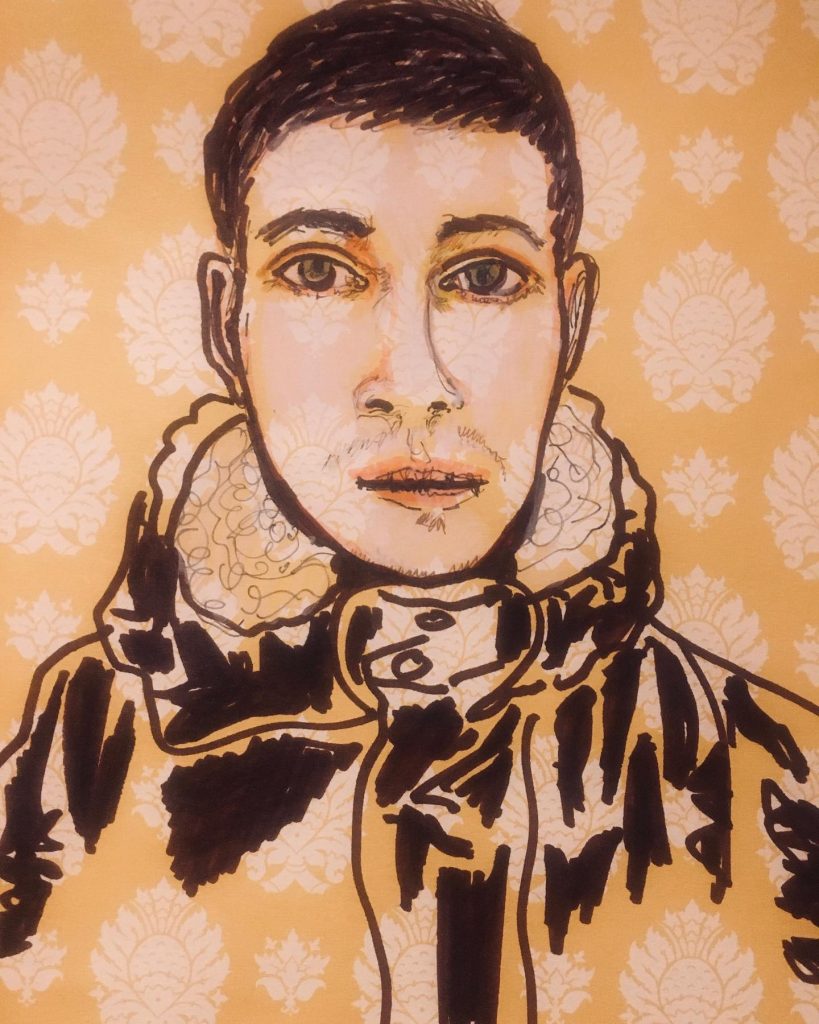

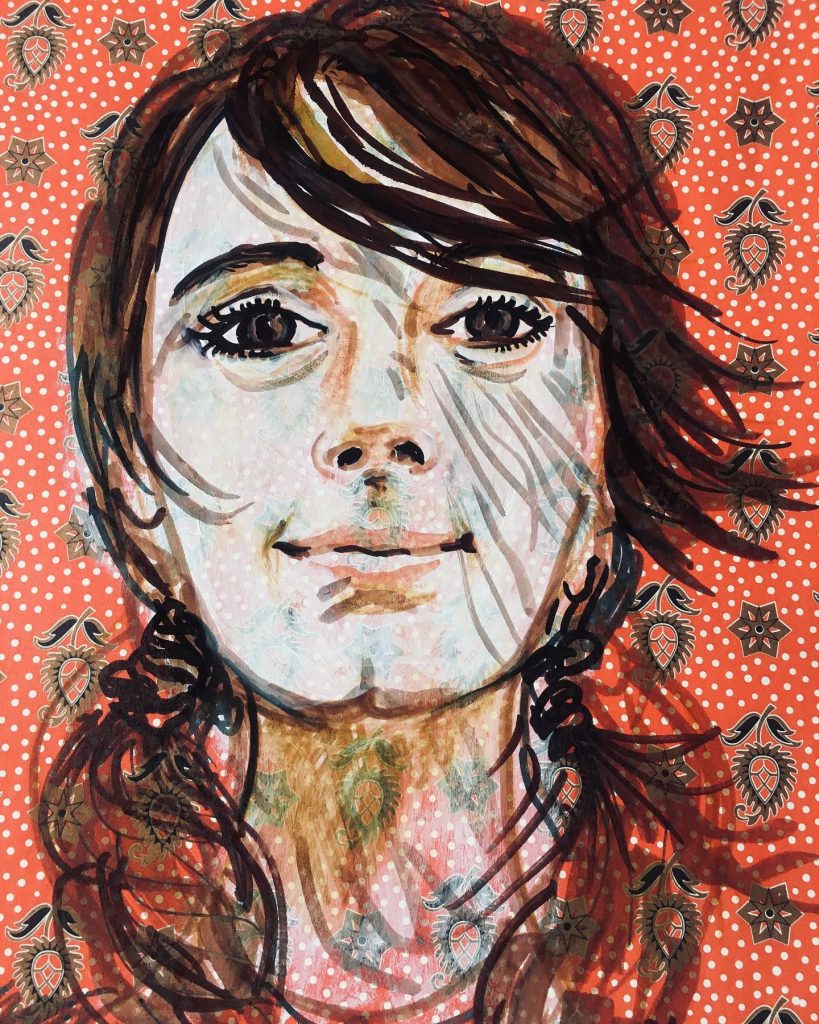

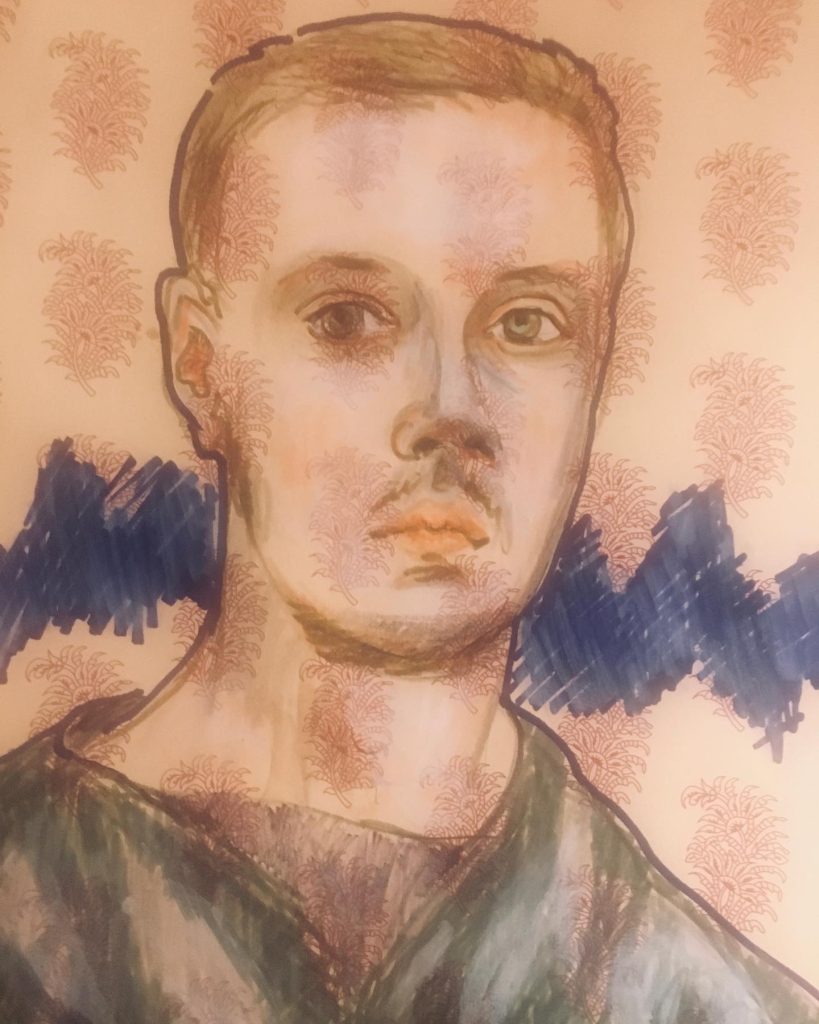

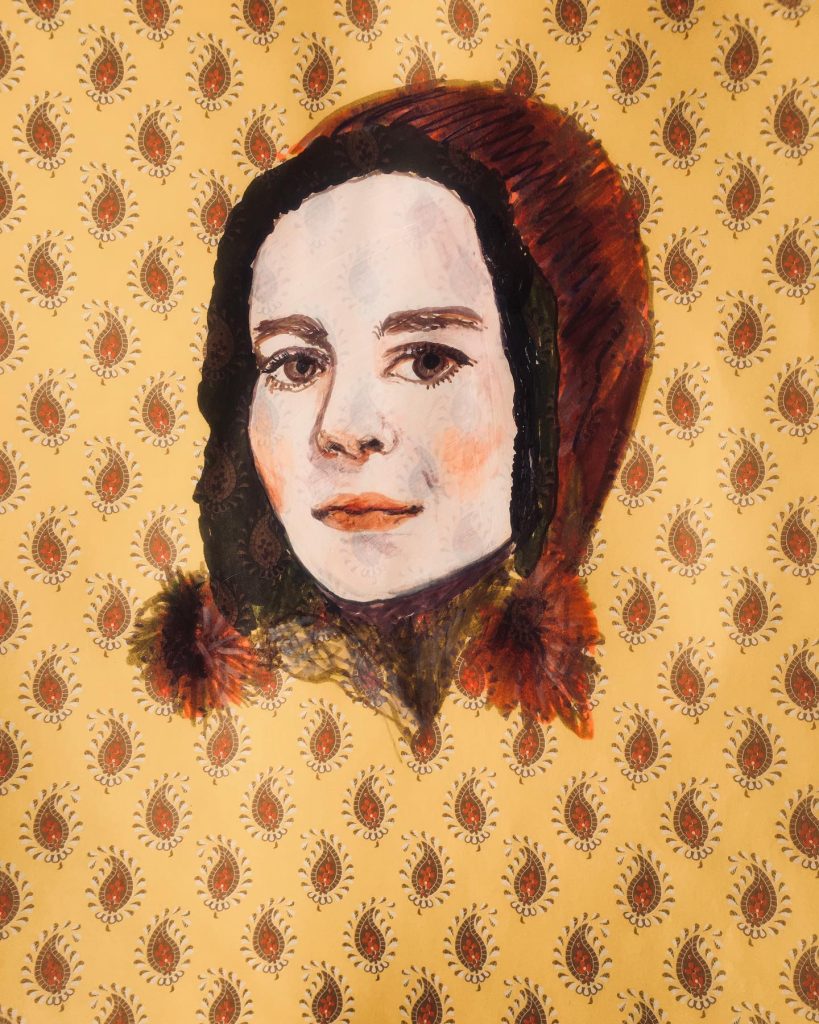

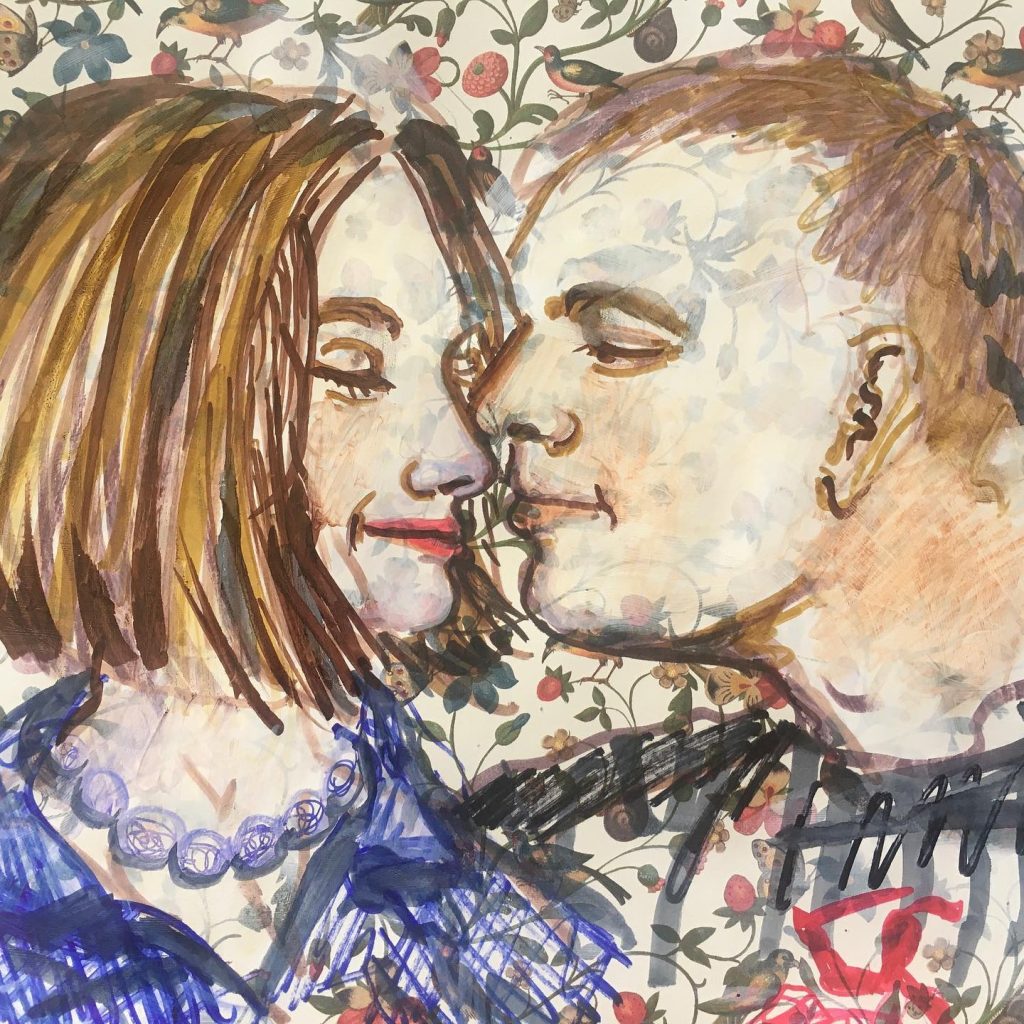

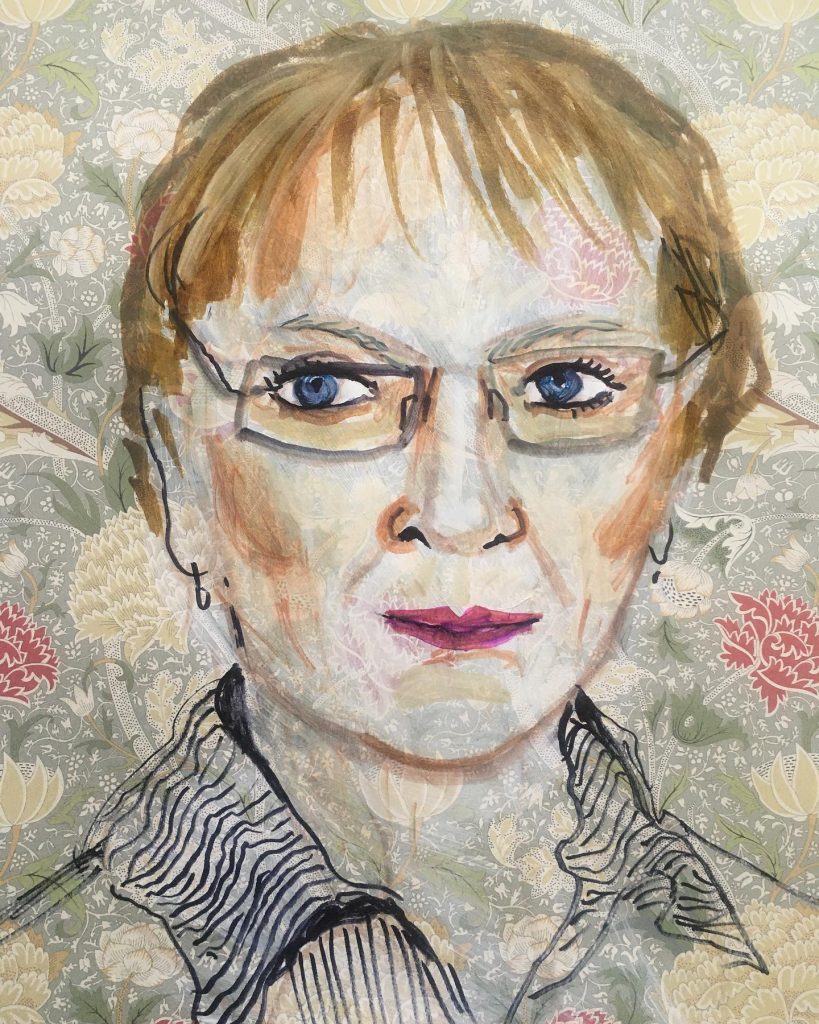

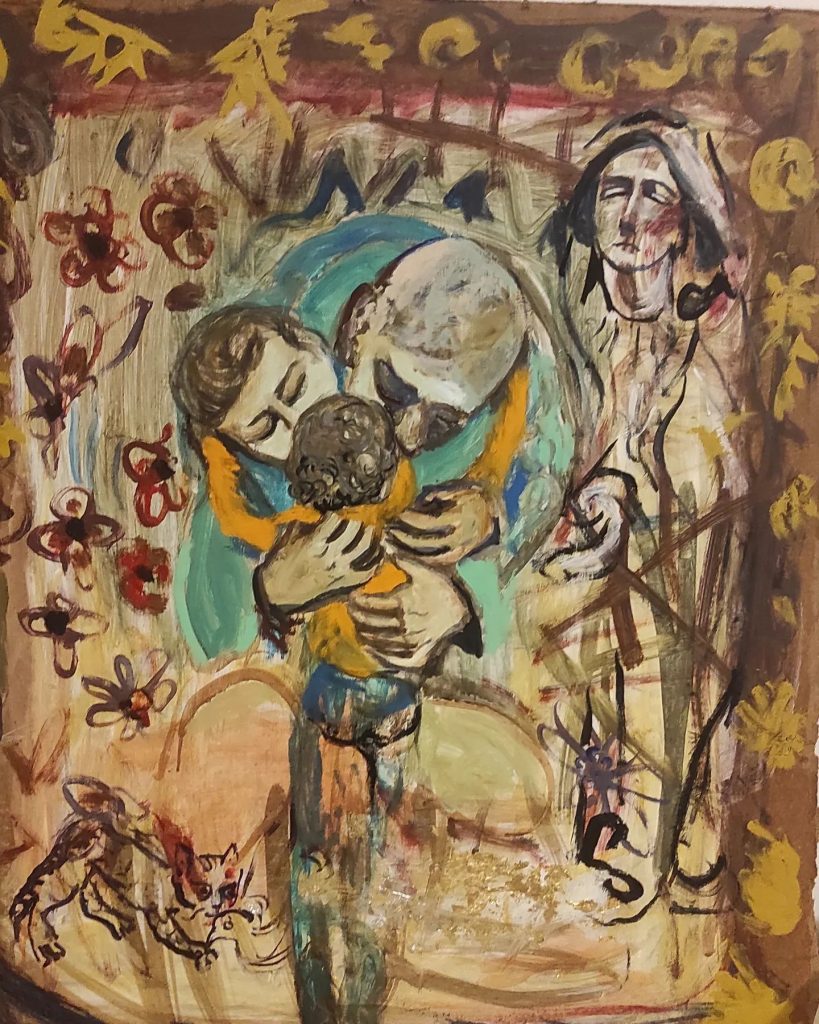

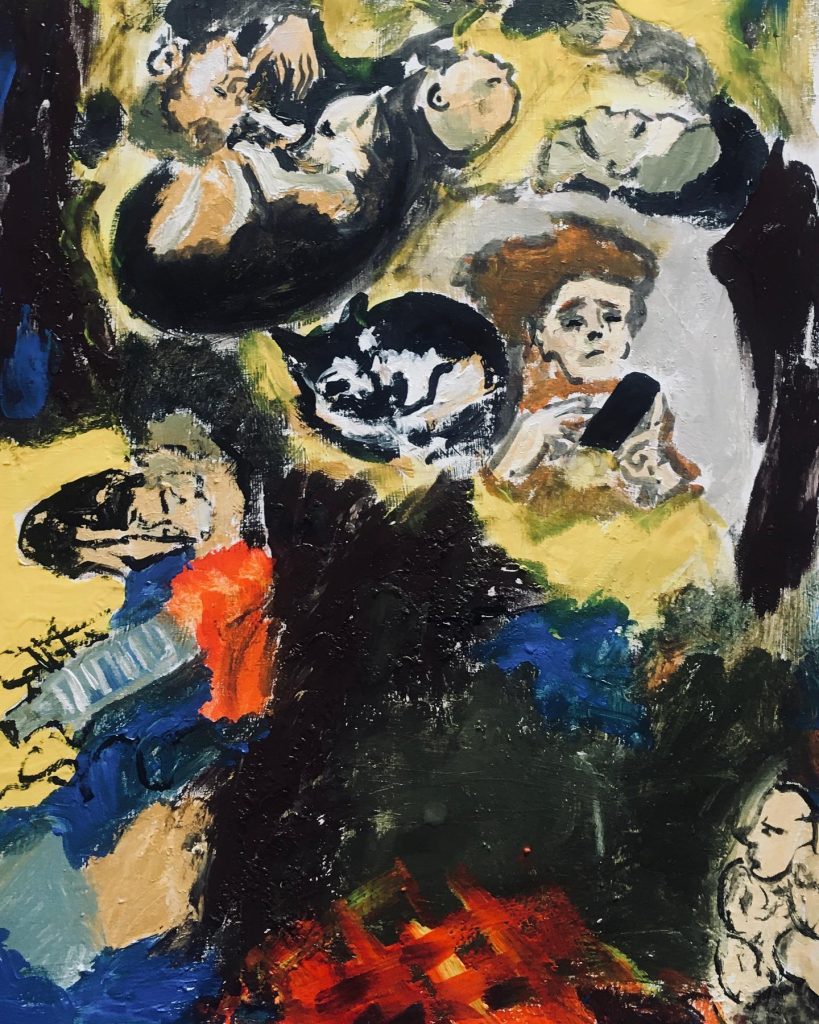

— To be honest, I’m not a portraitist. At first I painted saints, icons, and then I started to paint portraits, and not the other way around, and I’m glad it went this way. Portrait artists are people who are able to pinpoint a person’s character quite accurately. But I had a slightly different vision or a concept on how to portray Belarusian political prisoners, which I started doing in 2020. The important thing was that at a certain point I got rid of the inner feeling of “write so that someone will like it”, and it became easier for me. After all, the portraits of prisoners are not portraits in the full sense, they are “icons” of the Belarusian revolution… There is a large amount of artistic convention in them.

They don’t always look like the political prisoners themselves – I didn’t see them in person, but I painted them based on the pictures I found on the Internet, most often they were pictures of a bad quality… This made it quite difficult to make a portrait which would look similar to the original. I would really like to ask my heroes to forgive me if they see themselves differently… So my portraits are delivered in this artistic style, it is an avant-garde art in some sense. My goal is not to forget about prisoners but to remind others about them by any means available… There are completely different artistic tasks here if you are to start comparing it to a classical portrait school. In this sense, I think it is very good that myself, who is not a portraitist, started painting prisoners.

— So, for you, painting icons and portraits of political prisoners are essentially similar processes?

— When you paint icons you pay more attention to your inner state, feelings and you try to avoid self-destruction… And it’s a very similar way in which I paint political prisoners – sometimes I need to keep silent, stay at home, stay in a certain virtue. In this way, I become their non-verbal voice, a technical mean of conveying their words and intentions. From this perspective, the processes differ a little.

— How do you choose who’s picture to paint?

— I start with reading on a general information available about a person, in most cases it is information provided by the human rights center “Viasna”. I am keeping a close eye on accessing more information from the center, as its workers/volunteers are still operating in every Belarusian city. I often draw prisoners after or before their trials or as soon as some information reaches us from behind the bars… Relatives of political prisoners and prisoners friends also get in touch with me – for example, I would paint a portrait of a prisoner but there are more people connected to the same case, and that is how my heroes “tell” me who else I should paint. But mostly I make decisions on the spot, randomly, I do lack a systematic approach… For me, there aren’t more or less “important” political prisoners. I choose those for whom I feel empathy, the human factor is crucial here… I can be impressed by someone’s eyes or their words…. There wasn’t a time yet where I wouldn’t want to paint somebody.

— Do you follow the work of other artists of the Belarusian protest movement?

— Yes, of course, but their work is often very different to mine and I don’t always have a positive attitude towards them. For example, this winter there was an exhibition in Warsaw with a stand with the so-called “penitential videos” <videos of political prisoners being made to acknowledge, or “repent” of their offence in front of the camera>. I don’t understand it, to me it’s unethical, I couldn’t watch it. I do not understand the film director Andrej Kurejčyk, who is now making series about the events in Akrestina <the infamous detention center in Minsk>, when nothing has changed since August 2020, neither in prisons nor in the country, we are still living in the moment of pain and trauma. I do not understand the message of these people. Mine is completely different and it’s not based on empty hype.

— Do you feel a connection with the people you paint?

— Imagine that there is a person who is a complete stranger to you, but you know the colour of their eyes, you gaze into them; your mind, your life is being taken over by their features. They are no longer strangers to me… I believe and feel that there is indeed some kind of connection, even at a distance.

— Who was the recent person who’s portrait you painted?

— Pavel Sieviaryniec. However, this is a third portrait of him that I have created, because… Pavel is the Man… And he has been behind bars for more than 1000 days now…

— How many prisoners have you already painted?

— About 500…? I can’t keep up… In 2020, when it started, there were less than 100, and now there are over 1500; and these are only those who got recognised as political prisoners by the “Viasna” workers. Other associations of human rights defenders, such as Dissidentby, talk about more than 1,750 people, but in reality there are 3-4 times more than these figures because we simply do not know about some. A lot of people are being charged with “criminal” “political” articles, despite the fact that we all know that these people are being kept in prisons because they stood up to the regime.

— Do the prototypes manage to see their portraits?

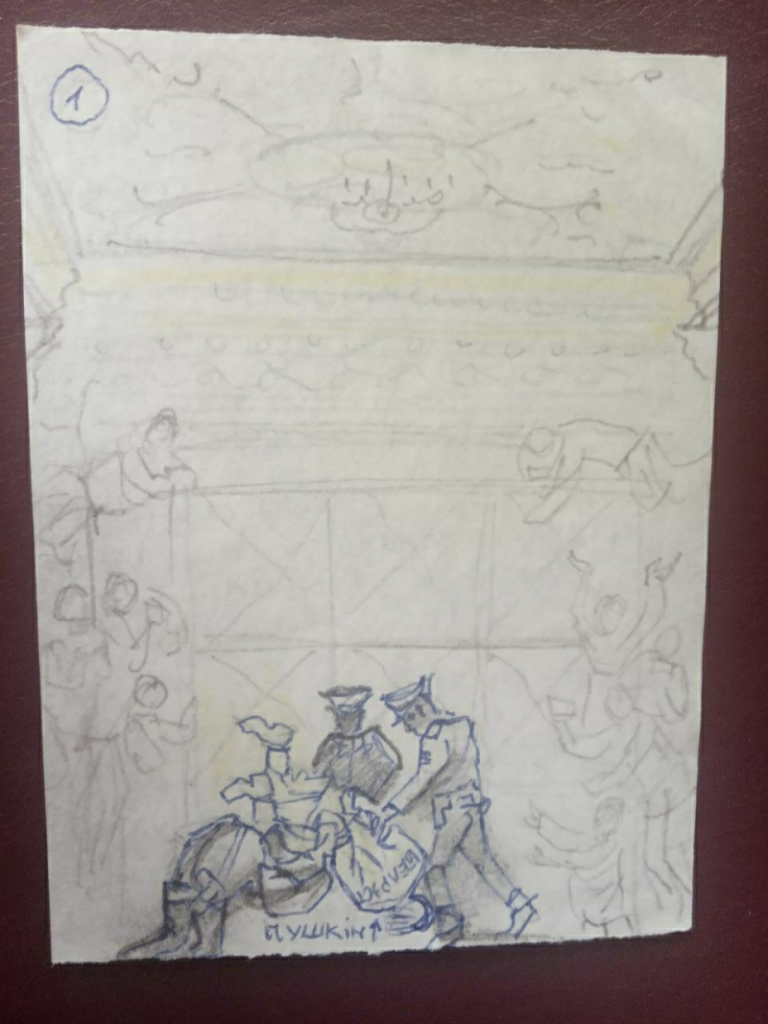

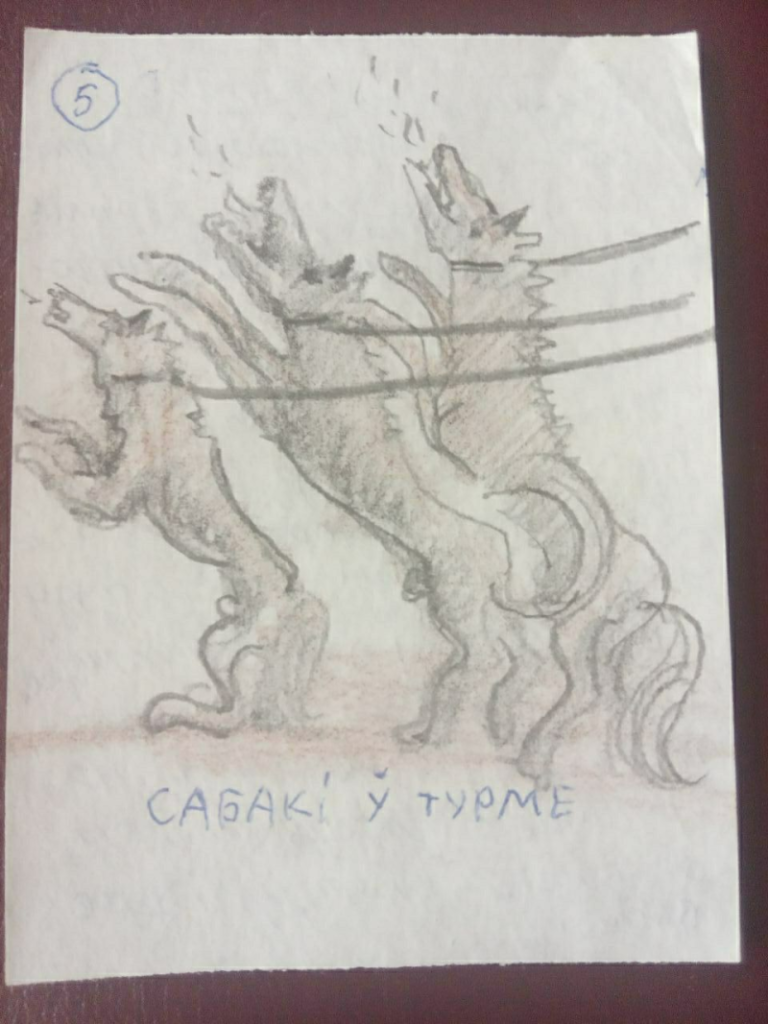

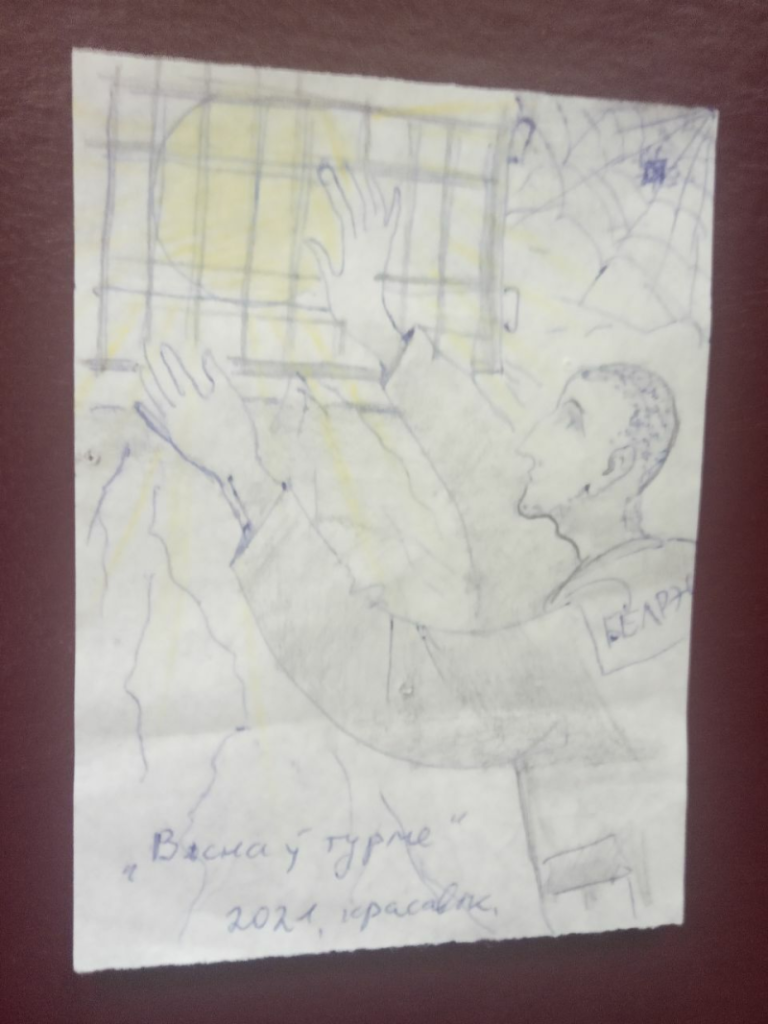

— It is important for me to let them know that they are remembered, they are being painted… Sometimes it is possible to pass a portrait even “there” <to prisons and detention centers>… Often these attempts fail, as my work doesn’t pass the censorship. But sometimes my portraits seem to be viewed as “children’s drawings” so often that makes it easier to pass the censorship and reach the imprisoned. I draw portraits on a wallpaper as it is a least reminiscent of being viewed as something political. The painting style I chose is one of the ways to overcome the obstacles….

— Is that why you choose this material [scraps of wallpaper]?

— Not just that. I gave up white sheets of paper so that our prisoners would not be remembered against the background of the grey door with the inscription “The normal position of the door is closed” when “repentances” might be getting knocked out of them for the camera… We want them to be remembered in portraits being happy with no fear and pain in their eyes. Even more than that, we know that they are being tortured behind bars, the conditions of detention are constantly deteriorating, and they definitely look different than in the “pre-prison” photos. This makes the process of “witnessing through portraits” to be a very difficult one emotionally. I choose wallpaper as a material, because there is no wallpaper in prisons, there are monochrome walls there and these walls are what the prisoners want to get rid of the most. Therefore, the background for their portraits adds this kind of coziness, life and colours, cheerful patterns; everything that is the antithesis of a prison’s greyness and faceless routine. They are all colourless in prisons… I can’t look at the pictures I see “from there” without pain. The works of Alieś Puškin, for example, simply break my heart…

— Is it expensive to produce portraits on such a mass scale?

— No one asks me such questions. I do run out of art materials quite quickly, and it is impossible to calculate exactly how much of it is being used. Sometimes, the above-mentioned wallpaper or scrapbooking paper is available for free, which is a great joy for me, but it is not always this way. Therefore, when I go, for example, to buy bread and milk, I also buy markers and other art supplies. So this became a regular expense for my household budget. Because this is now a regular affair… I have not been calculating my art expenses for a long time so I am not going to loose my sleep over it now.

— Why the theme of political prisoners is so important to you? Is it something personal?

— My great-grandfather Nikanor Kazimiravič Jaraševič was a political prisoner too. He was destroyed by the same system… His father and brothers were also killed… We don’t even have the exact place of their burial. I just can’t remain silent, that is simply impossible… I don’t know whether I would have had the courage not to remain silent if I had not had an example of this pain in my family… We have been suffering and keeping silent for a hundred years now. There created a critical mass of family history of pain and suffering, to which the recent events in Belarus and then in Ukraine have been added… I am not a courageous or brave person at all… But my family is an example of strength and courage, as once they were deprived of their fundamental rights. Therefore, now all my human and Christian empathy is set in this direction. Also, what I do and have done is an example to my children, they see that this is the center of my life today, and not just something should worry them. I believe that my activity is a way and an example of how to respond to what is happening in Belarus today.

— How did your life change since February 24th , 2022, including your creative life?

— It has changed completely. I remember the video of long chains of military equipment in Mačuliščy [Belarus] before February 24th , and how I cried back then, because it was obvious that those were no longer “military exercises”. On the 24th, I was woken up at 5 o’clock in the morning and the very next day refugees from Ukraine started to appear in Warsaw. Then there was no time to think about it, because I I became a volunteer from day one.

— What kind of experience was it?

— Before the war I worked at the Wolski Cultural Center in Warsaw, mainly with Belarusian children. After the war began, I managed to convince the people there we should start supporting arriving women and children from Ukraine. I painted the walls in the centre I worked 24/7 to manage this. The premises were used to welcome refugees from Ukraine. Helping them, I “shuttled” between the railway station and this center. Someone had to be accommodated in Warsaw, someone had to be helped to move on, someone to draw with, talk to or just listen to, some needing help looking for their relatives… A very moving experience. I devoted all my time to this at the time.

— How did the Ukrainians perceive you knowing that you were a Belarusian?

— It differed. I can say from personal experience that here, in Warsaw, you can give away your last shirt, but still you will always remain a foreigner from that country which launches the missiles. It is worth knowing and that if you have an internal resource, to not complain about the lack of any gratitude and just continue to help. By the way, I painted portraits of Ukrainian refugees, they made their way to an exhibition; and then no one returned these portraits to me, they were taken away by the people who were drawn on the portraits. Ukrainians are deeply traumatised and because of that I forgive them and understand the way they act. I would like to add that I have many friends in Ukraine, with whom we have excellent relations,and we support and understand each other very deeply.

— Do you continue helping refugees now?

— Yes, but not in such a volume. I teach Ukrainian and Belarusian children to draw. I also work with the most vulnerable group of refugees – the Ukrainian Gypsy children, who fled to Poland and who by their nature do not integrate well into society. Most often these children do not even go to school.

— What are you dreamimg about?

— To go back home. I have seen paintings by Chagall, Soutine, and their nostalgia resonates with me. I know for sure that I will always see my native plot of land, my corner with Belarusian nature, it will transform into a dream for me. We will be back. And I will begin drawing all this beauty – flowers, nature, curtains on the windows, friends, well, anything. But this is after the victory. Now I’m a bit of a “soldier” and art is my weapon… And afterwards I’ll go to Nioman [Belarusian river], look for white butterbur flowers, paint oak trees and a nightingale on an oak tree… I’m a tree person, I root a lot, and I’d rather stay in one place and not go anywhere. I’m like a hobbit…

I wish that the war in Ukraine would end soon…

I also dream of meeting those whom I draw. When they will get released, I will paint them again, but not from a photo and in a different way this time. I imagine it as a completely different gallery with the same people, but now of those being free.

— Will these be portraits on new pieces of a wallpaper?

— These will be portraits on white sheets of paper which we will fill with joy and happiness.

You can view the works of Xisha Aniolava on her Instagram.