“I am here for my faith in God.” Former political prisoner Andrei Krylov on the fate of Catholic priests Henryk Okolotowicz and Andrzej Juchniewicz and KGB pressure

Organisation"Christian Vision"

Belarusian inter-Christian association, created during peaceful protests of 2020.

Information about the «Christian Vision». Founding statement of the «Christian Vision» Working Group. The mission of the «Christian Vision».

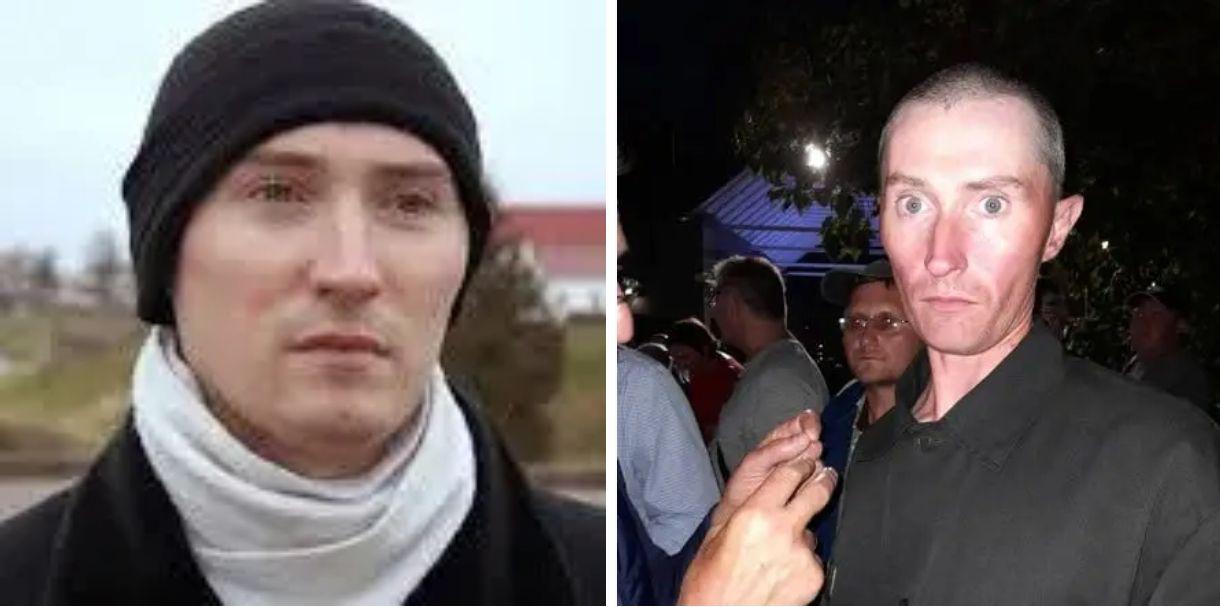

On September 11, 2025, among the 52 released political prisoners was Andrei Krylou — an activist sentenced to five years in prison on fabricated charges of “organizing mass riots.” Since late 2023, he had been serving his sentence in Correctional Colony No. 2 in Babruysk, where two Catholic priests and political prisoners are also held — Fr. Henryk Okolotowicz and Fr. Andrzej Juchniewicz. The former was charged with “treason against the state,” while the latter, after several months of torture for political reasons, had his case reclassified under articles related to the sexual integrity of minors.

At a press conference held shortly after his release, Krylou drew public and media attention to the situation of these two clergy members, emphasizing the urgent need for their release. In an interview with Christian Vision, he described in detail the conditions of their imprisonment, the fabricated charges of treason against Fr. Okolotowicz, and the attempts by the KGB to pressure him — in particular, to involve him in a provocation against the Apostolic Nuncio to Belarus, Archbishop Ignazio Ceffalia. Fr. Okolotowicz was arrested after being lured to a cemetery near Valožyn, where he was told he would perform a funeral rite. He himself stated that he considers himself a hostage: “I am here for my faith in God.”

– Yesterday, during the press conference of recently released political prisoners, you mentioned that you met Catholic priests who are also political prisoners while in detention. Were they Fr. Henryk Okolotowicz and Fr. Andrzej Juchniewicz, or someone else?

Yes, that’s right — two Catholic priests, both political prisoners: Fr. Henryk Okolotowicz and Fr. Andrzej Juchniewicz. They are both held in Penal Colony No. 2 in Babruysk.

But I know more about Okolotowicz.

I didn’t manage to speak with Andrzej — he has a “low status” in prison.

He’s being held under articles related to sexual violence — something from Article 166, 167, maybe 168 or 169, I can’t recall the exact charges. That status in prison is what they call the “lowest caste” — the so-called petukhi (literally “roosters”). I want to clarify: in our colony, there’s no actual sexual violence happening. Only in extreme situations, maybe the KGB instigates something through the worst inmates. But no, there’s no systematic sexual assault of man by another man.

Andrzej is a kind, gentle man. But he was always separated from me — by other inmates of that status. Whenever I tried to approach him, others would immediately say: “Why are you talking to him? What do you want from him?” Perhaps they were trying to protect him, maybe they thought I wanted to speak with him as an aggressor. I don’t know.

So I can only really speak about Okolotowicz.

– Did Fr. Henryk tell you how and why he was detained? What happened?

According to him, someone called his phone and told him a woman had died and asked him to perform a Catholic funeral rite at the cemetery. They said the coffin would be brought there, people would be present, and that he would be paid at the cemetery after the service.

He went to the cemetery — this was near Valožyn, where his parish is located — and saw several minivans parked, with people standing around. These people, as it turned out, were KGB agents, wearing trench coats. Five or six people, maybe, some vans.

And so he arrived and saw some minivans parked at the cemetery. This was in Valožyn, somewhere near Valožyn, in the vicinity of Valožyn — his parish was in Valožyn. The parish was in Valožyn, and therefore the parishioners were from Valožyn. So he arrived at the cemetery as instructed, and there were some vans, people were there, but — as it turned out later — these people were KGB agents. They were standing in trench coats at the cemetery, maybe five or six of them, maybe a couple of vans, I don’t know exactly.

He approached them and asked, like: “Where’s the coffin? Who’s being buried? What is this?” And they replied: “There’s no funeral here, you’re here for other reasons,” and so on. And then they took him. I don’t remember exactly how. There were a lot of men, and he was alone, already 60 years old. So, they took him — I can’t say for sure, but they most likely put him in handcuffs and put a black helmet on his head, so no one could recognize him, so no one could try to free him or attack the van to rescue him. That’s exactly why they do it — so that no one can see who is being taken, where, and by whom.

– What exactly was he charged with? What does the accusation of “treason” mean in his case?

According to him, the essence of the accusation — they charged him, and in the verdict it says that he caused material damage in the amount of one million euros. They took away the cars from his parish, including the car he drove to the cemetery, and everything that the Vatican had given him — some funds, transferred to him, I don’t know exactly, maybe it’s his assumption, but they took about 250, 270, maybe 280 thousand euros from him.

So, that part is clear. Then, during that period, he received a document stating that — taking into account the money we’ve already confiscated from you — out of the one million euros, you still need to pay the remaining amount in Belarusian rubles, which came out to about one million seven hundred and eighty Belarusian rubles. At that time, the euro was about 4 rubles, so you need to convert it to understand how much is left to pay.

And the accusation against Okolotowicz, according to him, was something like this: supposedly, he made some airplanes that flew off somewhere to change direction — for what reason, I don’t know — and he supposedly directed those Russian and Belarusian airplanes to fly in some other, opposite direction.

And in doing so, he supposedly committed a crime — what’s it called — the crime of treason against the state. He allegedly redirected the military, aircraft, and the whole air force in the opposite direction from where they were supposed to go. Somehow, he supposedly launched all the planes of Russia and Belarus, and they flew off on some kind of complex mission. What kind of accusation is that?

Officers from the KGB came to see him — most likely to try to force him to denounce his parishioners or other Catholic clergy.

And in the summer, they took him — by prison transfer — probably for 3 or 4 weeks, to Minsk, to the KGB pre-trial detention center. There, they gave him some documents to read, and apparently asked him to sign them — something like a court-related acknowledgment. But the transfer itself, this whole transport process — it’s incredibly stressful, seriously traumatic. As they say, two moves are equal to one fire, and one prison transfer is like ten fires. It really hits your nerves.

So they brought him there to sign some document — most likely a court paper. Some document that, they said, couldn’t be sent by mail or courier because it was a top-secret document of great importance, so they had to bring him in person.

This all happened over the course of June.

And now I’ll tell you what happened afterward. After he returned — about a month later — back to Penal Colony No. 2 in Babruysk, they called him in again. They told him that KGB officers would come to speak with him.

And the conversation went like this. They said, “You owe us a million euros. You understand yourself that this stuff with the airplanes and the million euros — it has as much to do with you as I have to do with ballet. It’s all nonsense, you know that. But just sign these papers, and we’ll let you go. We’re not asking anything else from you.”

And the documents — this is what Okolotowicz himself told me — contained approximately the following: The KGB was requesting that once he was reinstated as a priest in Valožyn, he should invite the Vatican’s ambassador — the Apostolic Nuncio — to visit him, and then secretly, as if “by accident,” hand the nuncio a flash drive. In other words, they wanted to fabricate a kompromat operation against the nuncio.But Okolotowicz refused.

He said he told them: “Look, I’ve studied for fifteen to eighteen years just to become a priest. I’ve even defended a doctoral dissertation. During my training and internships, I served in nearly every country in Europe. I served right here in Babrujsk for ten years. I’ve been serving in Valožyn for fifteen. Everything in me is focused on the work of the Church and of God. My whole mind is filled with God. And what you’re asking of me — that’s a crime. I cannot betray God, just as I cannot carry out what you’re asking.” But they told him: “We will come back to you many more times — maybe you’ll change your mind. Maybe you’ll agree to do it.”

– What are his conditions in the colony?

He’s holding up — doing okay. He’s got some health issues, I don’t remember exactly what. But I want to say — he’s staying strong, he’s holding on. The pain isn’t too severe. But he really needs to be released.

He’s a great man, really, a person of high standing.

He’s not being badly harassed in the colony by the staff — although they could, for example, deliberately accuse you of not greeting properly, of not following the required format: “Comrade Officer, I am so-and-so, born in such-and-such year, convicted under such-and-such article, registered under the profile ‘extremist and other destructive activity.’”

He can request to go to the medical unit, and they do let him in. He’s ill with something, has some kind of dietary issues or restrictions. But he receives all the required products, everything allowed under the regime provisions.

As with all political prisoners, only relatives are allowed to write to him. He was banned from correspondence — I don’t remember for how many years, he told me once, but I didn’t memorize it, didn’t need to. From the time he was detained, the first letter from his brother eventually arrived — maybe after a year, maybe two, I’m not sure exactly. That was the first letter that reached him after his arrest. Then, a couple of weeks later, a second letter arrived — just an empty envelope. And a few days later, I saw the officer, Astreyka, hand him the actual letter. It had supposedly been “misplaced,” but in reality, they had inspected it — to see what his brother had written.

That letter — Fr. Henryk told me himself — said that somewhere in Nigeria or some other place, a Catholic priest had been detained. They tried to deport him, but he refused to leave, and he was sentenced — 26 years. Then the Vatican fought for him, and eventually — after about a year — they managed to get him released and expelled from the country. The Vatican managed to push that through only after a year. There was also some other valuable information in the letter, but I don’t remember what it was.

That’s the kind of man Okolotowicz is — he doesn’t really petition for himself.

If someone has connections in the Department of Corrections (DIN) or tries to file a complaint with them, they often get punished in retaliation — because they went over the heads of the local administration. But the recent trend is: if someone complains to higher authorities, they become untouchable. The staff are afraid to mess with them, so they stop inventing punishments. Normally, they’ll say something like: you weren’t shaved properly — even if you were. Or that you smoked in an unauthorized place — that’s what they do to people registered under the “tenth profile” (that’s what they call political prisoners — not “political prisoners,” but “tenth profile”: “extremist and other destructive activity”).

Usually the officer will call you in and say: “Write a statement saying you smoked in an unauthorized place. Or that you weren’t properly shaved. Write that you have bad eyesight and couldn’t see in the mirror. Or make something up — say you didn’t greet me. Just write something. Some violation. Whatever you want. Whatever’s better.” And so people write.

Everything is just covered in lies.

The system is massively bloated. There are too many staff, and they don’t do anything — they just pick on everyone, nitpick constantly, walk around trying to catch someone doing something. And they’re all scared of each other — scared for their ranks. When a higher-level inspection team arrives, they panic ten times, a hundred times more. They climb fences, crawl through mesh wiring — just to avoid running into them. If a commission is coming — two, five people — and there’s no gate nearby to escape through, they’ll climb through barbed wire just to avoid crossing paths. God forbid someone from the commission asks them a question they can’t answer — then they’ll be fired. They’re all idiots, frankly. Kind of dim. I mean the staff — the prison administration, the DIN people. The smarter ones don’t last long — they leave.

– Is he allowed to communicate with others or speak about faith? What about religious life in the colony?

No one ever prohibited me from speaking with him, and no one else was forbidden from approaching him either.

He gives advice — in a morally uplifting, spiritually beautiful way.

He says, for example, that one shouldn’t smoke, because, you know, there are people who already lose their grip on reality, who become unstable, and if they also smoke, it just destroys their brain even more. So, he gives this kind of advice — not in a pushy way, but as suggestions, if someone wants to hear it. And there was also this one guy — a Ministry of Internal Affairs officer, I think — who came up to him and said, “I remember when I was young — you were the one who married me.”

As for religious life, there is an Orthodox church on the grounds of Penal Colony No. 2. But political prisoners are strictly prohibited from attending.

Some convicted prisoners are allowed to go there if they’re registered. Many want to — there are lots of Catholics in the colony, I can tell you that. Many Catholics are convicted under various articles — murderers, fraudsters, and so on — but by religion, they are Catholics. They go to one particular spot, where it’s closer to the church, and at certain times every day, the bell rings three times — our Orthodox church bell. When the bell rings, the Catholics stand still, make the sign of the cross, and silently say their prayers. I also know that there are some Catholics who, in the morning, go stand in a corner of the exercise yard. That’s the local outdoor area — a fenced-off zone where we’re allowed to walk. And they stand there in the corner, silently praying. Of course, some of them approach the priest as well — they say Catholic prayers, they pray to God, to the Lord.

Henryk asked if he could attend that Orthodox church — or if he could at least be allowed to lead services, so that Catholic believers who wanted to could come to him. They told him this is absolutely forbidden.

That if even ordinary prisoners on the “political profile” are not allowed to attend the church, then a priest — all the more so — is not allowed to conduct anything.

People actually treat him quite well, by the way. But, as the priest explained to me, the way the state sees it is this: if Poland is arming itself, then Poland is an enemy — and therefore the Catholic Church is an enemy too. And the state believes it should push the Catholic Church out of Belarus just like Ukraine is now trying to push the Russian Orthodox Church out of Ukraine. That’s the tendency. And that’s why they organize all these setups and provocations.

– Did Fr. Okolotowicz submit a request for a pardon?

I don’t know for sure about a pardon. But

I doubt he could have submitted one — because he deeply believes that, as a convicted person, he is in fact a hostage, a captive. As he said: “I am here for my faith in God.”

– Why did you choose to draw attention specifically to the Catholic priests at the press conference?

Okolotowicz knew that I would soon be released — as of today, September 13, I had sixty days left to serve. And

he said: “Make every effort so that the media learn about all of this, so that everyone writes about it, so that attention is drawn to how many people have been unjustly convicted.”

He’s a person of high standing — a Doctor of Theology, studied for fifteen years, taught. He said that the only thing that can help is pressure. Not on the state of Belarus — but on the regime, which is a criminal one.

The only thing they fear is publicity — the media. That’s the only kind of pressure that works.

The world must be told, the Vatican must be told, so that they act, so that they help free people. The regime must be made to fear.