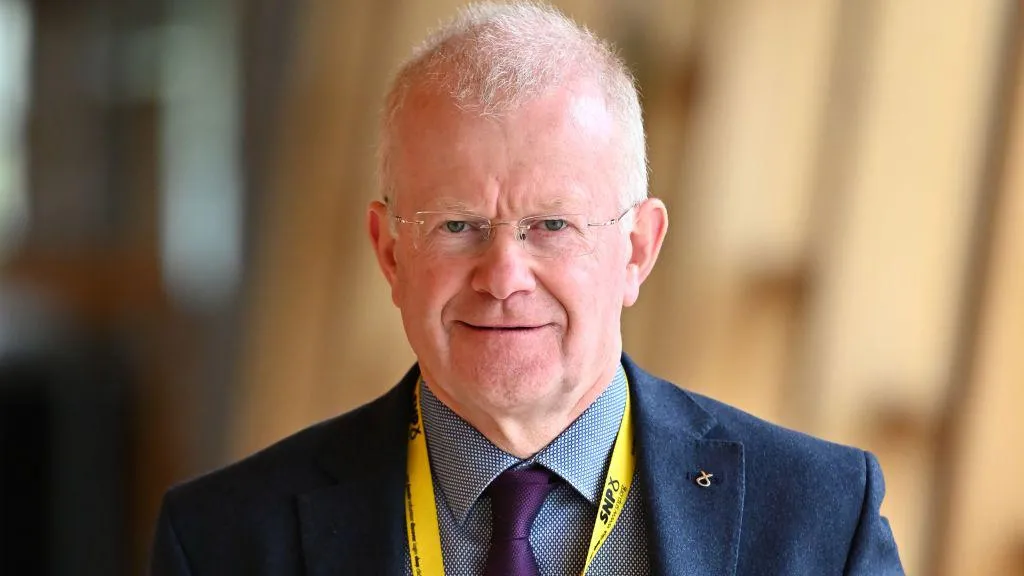

Belarus and Scotland: Building Bridges Through Scottish Parliamentarian John Mason’s Experience as a Symbolical God-Parent of the Recently Released Political Prisoner Mikalai Khila.

John Mason is a Member of the Scottish Parliament from Glasgow. He is known for his principled stance and willingness to speak openly on controversial matters. Formerly a member of the Scottish National Party, he now serves as an independent politician. In this interview, Mason reflects on the challenges of modern politics, his core values, and why independence and integrity matter more to him than party loyalty.

Mr. John Mason is the godparent of Mikalai Khila, Belarusian political prisoner and Christian who was recently released from prison and immediately deported to Lithuania. We spoke to John shortly before this event.

Natallia Harkovich (NH): Why is it important for you to act as the godparent for one of the political prisoners in a Belarusian prison?

John Mason MSP (JM): I am convinced that the Bible’s teaching is God’s teaching. This is why the Church is one body all over the world. Even if we have never met, we are like a family — brothers and sisters. Obviously, we can’t know everybody everywhere, but when there are opportunities to connect with someone, it’s a good idea. I lived in Nepal, where the Church was not exactly persecuted but still faced a lot of pressure. That experience developed in me an interest and sensitivity to such situations.

I became involved in a group in the Scottish Parliament with a particular focus on freedom of religion or belief. There I came across many individual cases — that’s how I got linked in with you. There is a limit to what any one person can do, but I pray and occasionally write to someone like Mikalai.

NH: How does your belief motivate you as a political actor?

JM: There are a lot of reasons why I’m in politics. I was in the Scottish National Party because I want Scottish independence, just like Belarusians want their independence. There’s a small number of us in the Scottish Parliament who are committed Christian believers. We strongly believe that the Church is one body worldwide. And just like with our physical body — if one part hurts, the whole body is affected.

The Church in Belarus and the Church in Scotland are one Church. Though we haven’t met or don’t know each other personally, they are still part of me. We are affected if others suffer, are persecuted, live in poverty, or starve. Of course, the Church doesn’t always get it right, and we don’t always care enough; instead, we can become very focused on our own matters.

There are a lot of needs in Glasgow and the rest of Scotland, but we should at least be aware and, I believe, pray more for the people in Belarus and elsewhere. We can use social media to raise awareness, with good input from Forum 181, which focuses on the ex-Soviet world. And we write letters. That’s just how things have worked out for me — to have these individual links as godparents to prisoners.

NH: What is most important or most painful for you when watching the Belarusian situation from afar?

JM: I feel for the church leaders and Christians there. I can see how difficult it is for them to know the right thing to do. They are under a lot of pressure, and being imprisoned may not always be the best course. In China, for many years, some Christians have worked more closely with the government in state-approved churches, both Catholic and others, while others maintained underground or informal unregistered churches and refused to work with the government. Sometimes there are tensions between Christians over this.

I feel for them. In Nepal we were not allowed to do certain things — how far could you push the boundaries? I’m sure it’s hard for many of them. Some will just follow the government no matter what. Some may be very antagonistic and do their own thing. But I’m sure there are many believers in the middle, including church leaders, who are really struggling to discern what is right. Even within churches and families they may disagree.

I feel for them, and that’s why I pray for them — for wisdom. The Bible tells us to pray for wisdom, and I do. Not every believer in Belarus needs to act in exactly the same way. We don’t need all the believers in prison. We need some people outside, perhaps being a little more careful. But it’s a hard position to be in.

NH: We know about the persecution of believers in the Soviet Union, and now we see a new type of persecution. When did you first recognise this new wave?

JM: I grew up during the Cold War, when there was clear persecution of Christian believers throughout the Communist world. And although the Soviet Union seemed to have opened up, in countries like China it has continued. We see, according to the organisation Open Doors2, that North Korea is the worst, and has been for a very long time.

The persecution of Christian believers varies around the world; it comes and goes in different countries. When I was growing up, it was very much about the Communist countries and their persecution. More recently, the focus has shifted to some Muslim-majority countries — Afghanistan, Saudi Arabia, even Pakistan — where Christians have suffered most.

Through your organisation and others like Forum 18, it’s become clear that in the former Soviet countries, certainly in Belarus but also in Kazakhstan and Kyrgyzstan, the requirement for church registration makes things very difficult. Sadly, persecution of Christians is continuing in many places.

NH: What would you consider the most significant successes of your political activity?

JM: One of the things I believe I’m meant to do is to challenge the establishment. I do that locally, for the whole of Scotland, and would do it anywhere in the world if the opportunity arose. I’ve been in politics since 1998 — for the last 27 years. I like to think I’ve asked a lot of the right questions.

Sometimes there’s great importance in asking questions. Everybody can stand up and shout about what is wrong, and there is a lot of wrong in the world. But asking questions and making people think affects those you’re talking to. Asking questions that maybe others don’t ask — that’s the kind of space I think I’ve occupied and, I hope, where I’ve had some impact and success over the years.

NH: Thank you very much for your time, for sharing and for your support of Christians in Belarus.

- Forum 18 is a Norwegian human rights organization that promotes religious freedom. The organization’s name is based on Article 18 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights. Forum 18 summarizes the article as: The right to believe, to worship and witness; the right to change one’s belief or religion; the right to join together and express one’s belief. The Christian Vision for Belarus is in contact with this human rights organisation (see, for example the material “BELARUS: Police take relatives’ DNA after KGB declares religious freedom group “extremist”” May, 7th, 2025). ↩︎

- Open Doors is a global, non-denominational Christian organization founded in 1955 to support persecuted Christians worldwide by providing Bibles, Christian literature, discipleship training, and practical aid like emergency relief and livelihood support. ↩︎