Catholicism’s accidental exile captures drama of post-Soviet world

ROME – Some people, it would appear, simply are born for exile. Sometimes it’s a firebrand personality constantly irking the powers that be, but in other cases it’s mostly bad luck, circumstance, and the fact that a given person is an inconvenient reminder of a system’s failures and blind spots even without trying.

The latter would seem to be the case for Archbishop Tadeusz Kondrusiewicz, the chief shepherd of Minsk in Belarus who’s currently in exile in Poland after being denied reentry into Belarus by the government of longtime President Alexander Lukashenko, dubbed “Europe’s last tyrant,” who’s currently facing massive street protests after a disputed reelection victory in early August.

Kondrusiewicz, born into an ethnic Polish family in Belarus in 1946, had been in Poland to take part in celebrations for annual celebrations in honor of the Madonna of Częstochowa. When he attempted to cross the border back into Belarus, he was turned away and accused by the Lukashenko regime of being in league with the protesters.

A message he delivered in mid-August may have provided the pretext.

“Our country is living through a difficult moment, which unfortunately already has been marked by the spilling of blood and thousands of arrests of citizens who’ve been brutally beaten for wanting to know the truth about the presidential elections of August 9,” he said.

It’s at least the third time in Kondrusiewicz’s life he’s either been pushed out of someplace or not allowed back in.

The first came as a young man, when he was kicked out of the Hrodna Pedagogical Institute in Belarussia because he was a Catholic, during an uptick in religious persecution under the Soviets. He eventually finished his education in Leningrad (St. Petersburg) and became a mechanical engineer, working in Lithuania, before switching gears and entering the seminary at the age of 30.

The second came under Pope emeritus Benedict XVI, when he was removed as the Archbishop of Moscow (technically, the “Archdiocese of the Mother of God at Moscow”) and sent back to Belarus in 2007.

The Vatican’s diplomatic elite had a policy, one that’s still very much in force, of long-term détente both with the Russian government and the Russian Orthodox Church, and Kondrusiewicz was judged to be an obstacle. That’s both for the mere fact of being Polish, and thus a reminder of Russian/Polish tensions (the Kremlin recently charged that the protests in Belarus are being engineered by Poland), and also because of his association with a controversial 2002 decision to erect four Catholic dioceses in Russia which the Orthodox saw as an encroachment on their canonical territory.

Behind the scenes, it was known that there were tensions between Kondrusiewicz and the Vatican representative in Russia at the time, Archbishop Antonio Mennini, who served from 2002 to 2010 and whose crowning achievement was the launch of full diplomatic relations between Russia and the Vatican in 2009. In service to that aim, Mennini pursued a policy of avoiding confrontation with either the Kremlin or the Patriarchate of Moscow, which sometimes chafed against Kondrusiewicz’s desire to promote the normal pastoral life of the Catholic Church in the country without necessarily worrying about the sensitivities of figures within the Patriarchate of Moscow.

When Kondrusiewicz was replaced with Italian Archbishop Paolo Pezzi, it was seen as a victory for the Mennini position, and his reassignment to Minsk was seen as a way of putting the Polish prelate on the sidelines.

Providence, however, often has a keen sense of irony, and so it is that a decade a half later, Kondrusiewicz now finds himself once again at the heart of the action in terms of the broad direction of the post-Soviet world.

For his part, Lukashenko has confirmed the ban on reentry, saying it’s not just Kondrusiewicz who’s being frozen out.

“He’s just the best-known,” Lukashenko said. “It’s not important whether someone is Catholic, Orthodox or Muslim, you have to respect the law. There’s a double responsibility when you mix the church and politics.”

Lukashenko believes Kondrusiewicz has been encouraging the protests, which have seen tens of thousands of Belarussians take to the streets. In just the first few days of the uprisings, international observers say that some 7,000 people were arrested and hundreds beaten by police and security forces, prompting charges of widespread human rights abuses.

To be clear, Kondrusiewicz is nobody’s idea of a hothead. He repeatedly called for calm after the protests erupted, and has even expressed sympathy for Lukashenko’s predicament, describing the resistance as the consequence of a new generation coming of age with broader experience of the world and different expectations, which, he says, “no one saw coming even a year ago.”

As for his present situation, Kondrusiewicz clearly doesn’t want to play the martyr.

“I’m almost 75, and before long I’ll present my resignation to the pope,” he said, referring to the age at which all Catholic bishops are required to offer their resignations; Kondrusiewicz will turn 75 in early January.

“I don’t like not being with my people, but I’m not going to do anything to rock the boat,” he said. “Some people [in the protests] have been carrying my picture around, but I say: ‘Let it drop, just go pray.’”

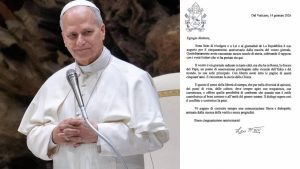

For the Vatican, to date neither Pope Francis nor the Secretariat of State have spoken publicly about his case, but in a recent interview Kondrusiewicz said he feels strong “moral support” from Rome.

It remains to be seen whether the resignation to which Kondrusiewicz referred will be accepted; his predecessor in Minsk, the late Cardinal Kazimierz Świątek, served until he was 91 (and he kept going as the apostolic administrator of another diocese in Belarus until he was 96.)

In the meantime, however, this accidental exile serves as a reminder that sometimes just being who you are can put you on the wrong side of those in power. Whether Kondrusiewicz is also on the wrong side of history, of course, is an entirely different question.

John L. Allen Jr. Sep 6, 2020